Android’s Bluetooth LE Reliability Problem

Building Bluetooth apps on Android has always been tricky. Those of us who have worked on Andriod since its earliest days have been hounded by frustrations of the platform. These range from buggy Bluetooth stacks to fragmentation caused by manufacturers that have to build their phones just a little differently.

Most complaints about Bluetooth on Android are vague and anecdotal. With no hard data to back up the problems, it is never clear if the real problem stems from operator, a buggy app, or the hardware of a crappy off-brand phone. It has always been easy to dismiss the complainers as malingerers. But months of real world data collection across a variety of devices provides evidence that Android itself is the real problem.

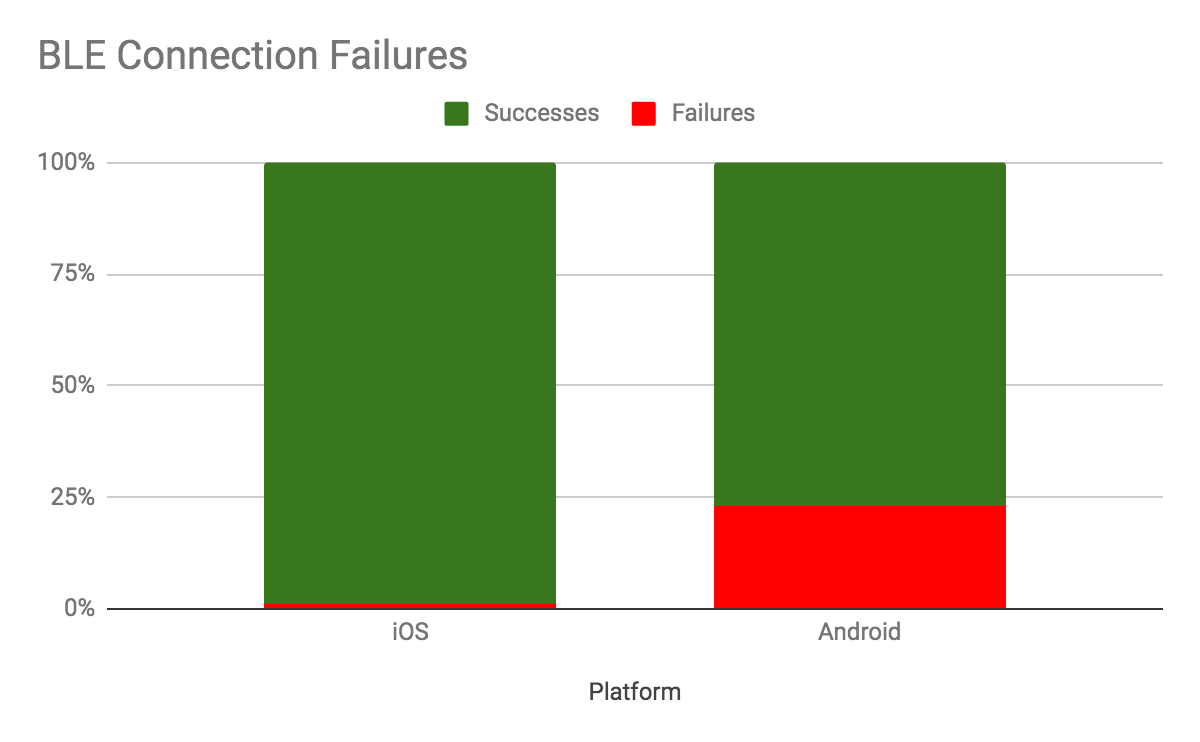

The data show that even at close range, Android Bluetooth connections fail a whopping 20 percent of the time, compared to less than 2 percent on iOS. This sizable difference is big enough to feel in daily use. On iOS, Bluetooth connection just work. On Android, they usually work, but they aren’t as reliable.

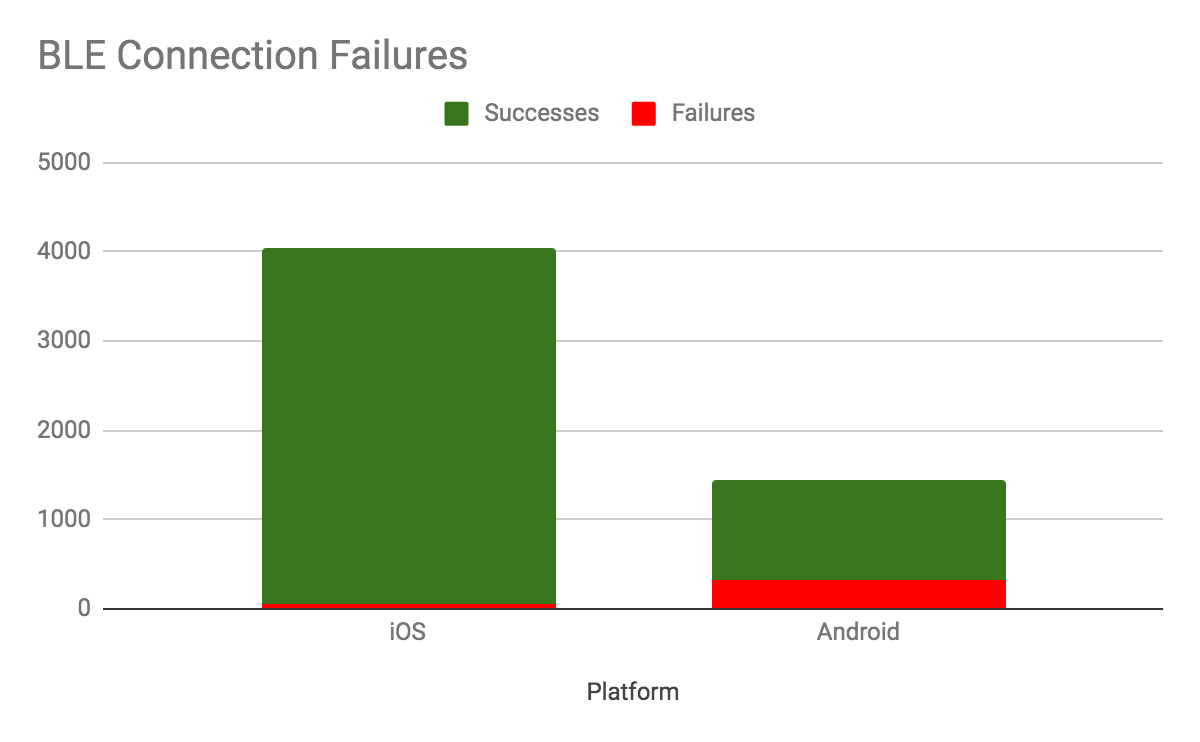

The first graph above shows the percentage success and failure rate on each platform. The second graph shows the raw counts of successes and failures recorded. The total numbers are lower on Android because most users are on the iOS platform.

Data Collection

Using a local automated parking system, I collected the data between late 2016 and early 2019. The system provides automated commercial garage access using mobile phones to open the entry and exit gates. The apps for iOS and Android use mobile data networks to authorize gate openings when a mobile network is available. But often times, when exiting a cavernous parking garage, cell connectivity is spotty at best. That’s where Bluetooth comes in. We fitted garages with LInux-based bluetooth relays near the exits hosting a custom Bluetooth LE GATT service. When the mobile app can’t reach the server, it connects to this Bluetooth service to authorize opening the gate, allowing the customer to exit the garage.

This usually works great. Within a couple of seconds of tapping an exit button, the gate simply goes up, and a happy customer drives away.

Sometimes, however, this fails. Anecdotal reports of drivers getting error messages (especially on Android) led me to collect metrics in the app and report them to a server.

The data collected include not just success/fail status, but the specific failure condition as well as the phone manufacturer, model, and operating system version. This allows us to compare failure rates across not just Android and iOS, but across different operating systems and versions.

The data show that there is no significant difference across different iPhone models and iOS versions. All perform quite well with very low failure rates of less than 2 percent.

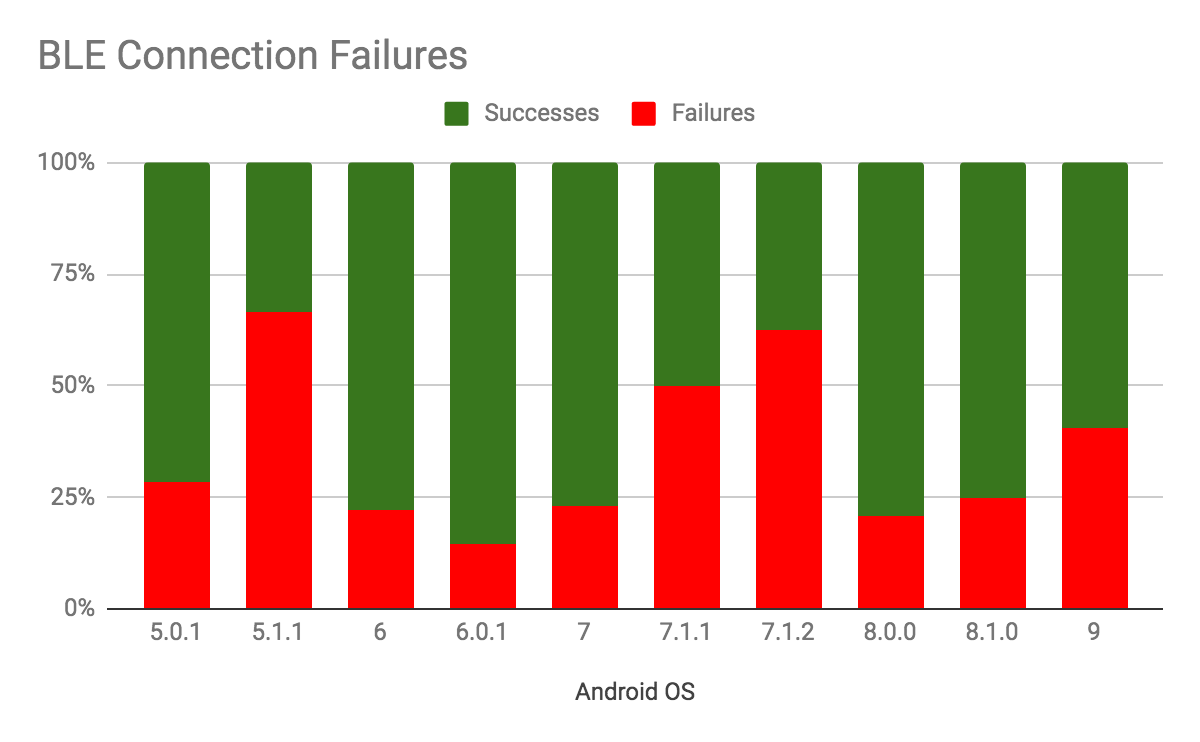

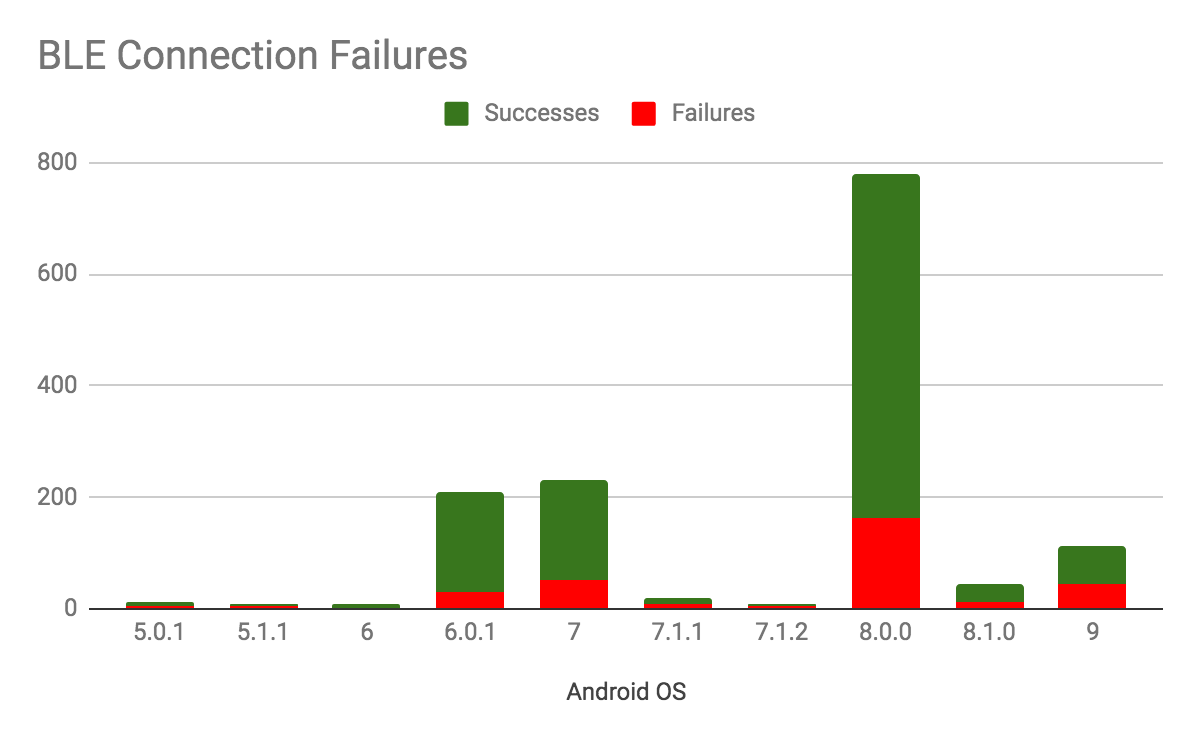

On Android, much higher failure rates are the norm, even on high end phones and newer operating system versions. Surprisingly, success rates on Android 6-9 are not noticeably better than Android 5. This is bad news as it indicates the situation on Android is not improving with newer operating system releases.

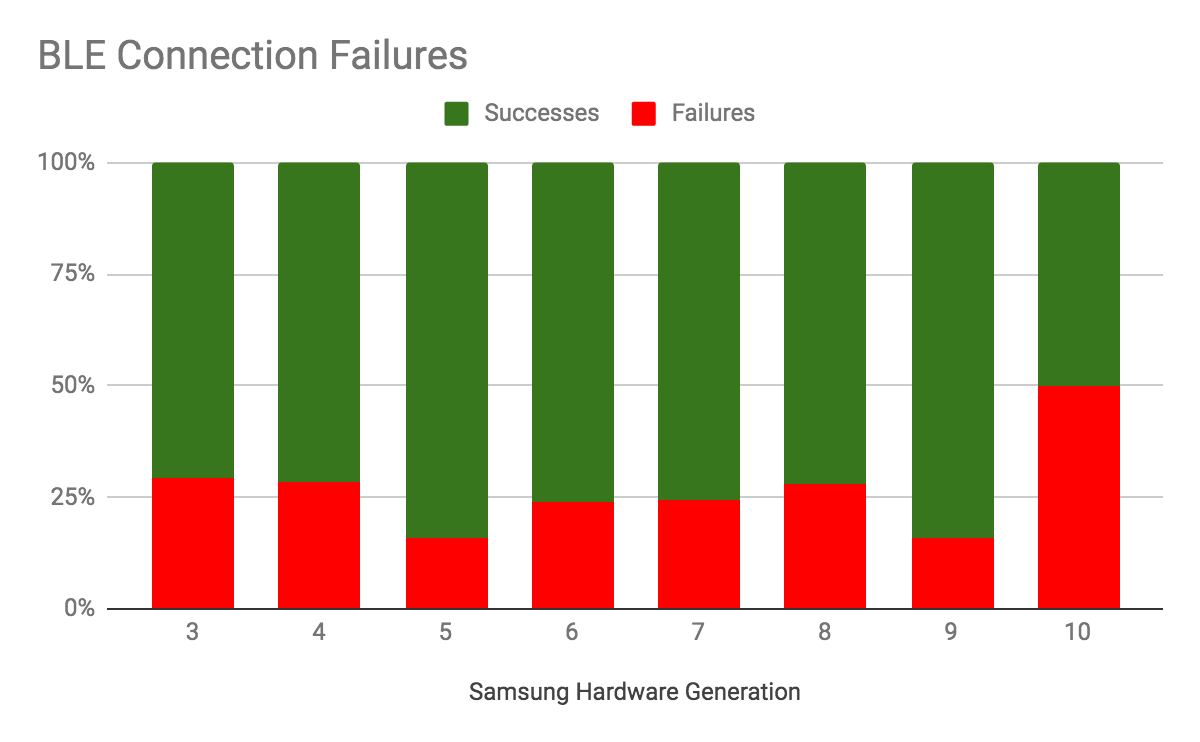

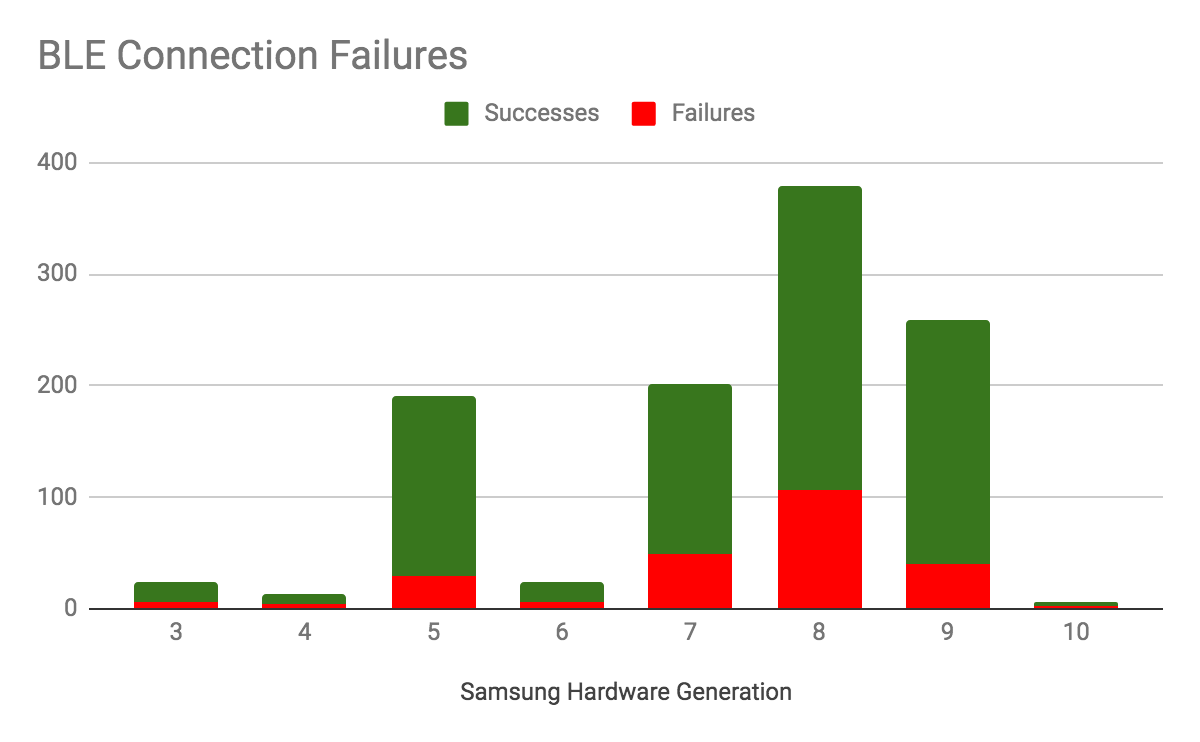

Newer Android hardware models also do not show reliability improvements. Grouping the Samsung data by hardware generation (e.g. Galaxy Note 8, Galaxy S8 Edge, and Galaxy S8 are lumped together as generation 8) show the failure rate is not improving.

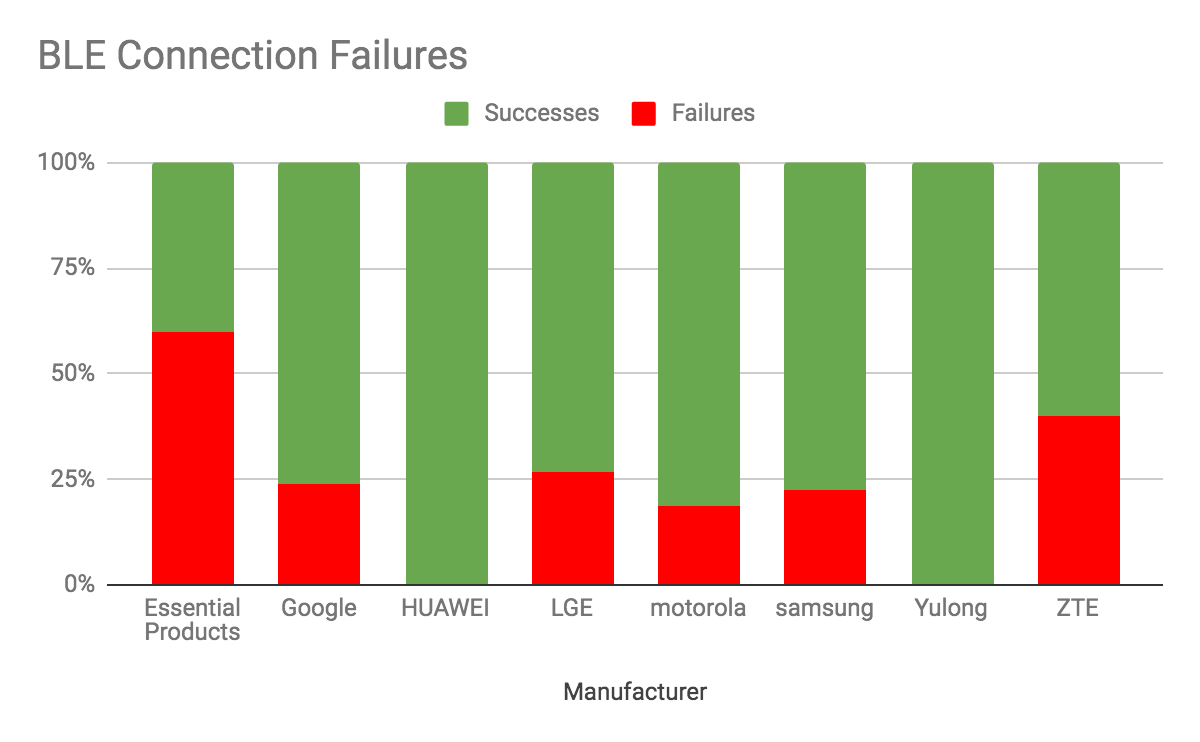

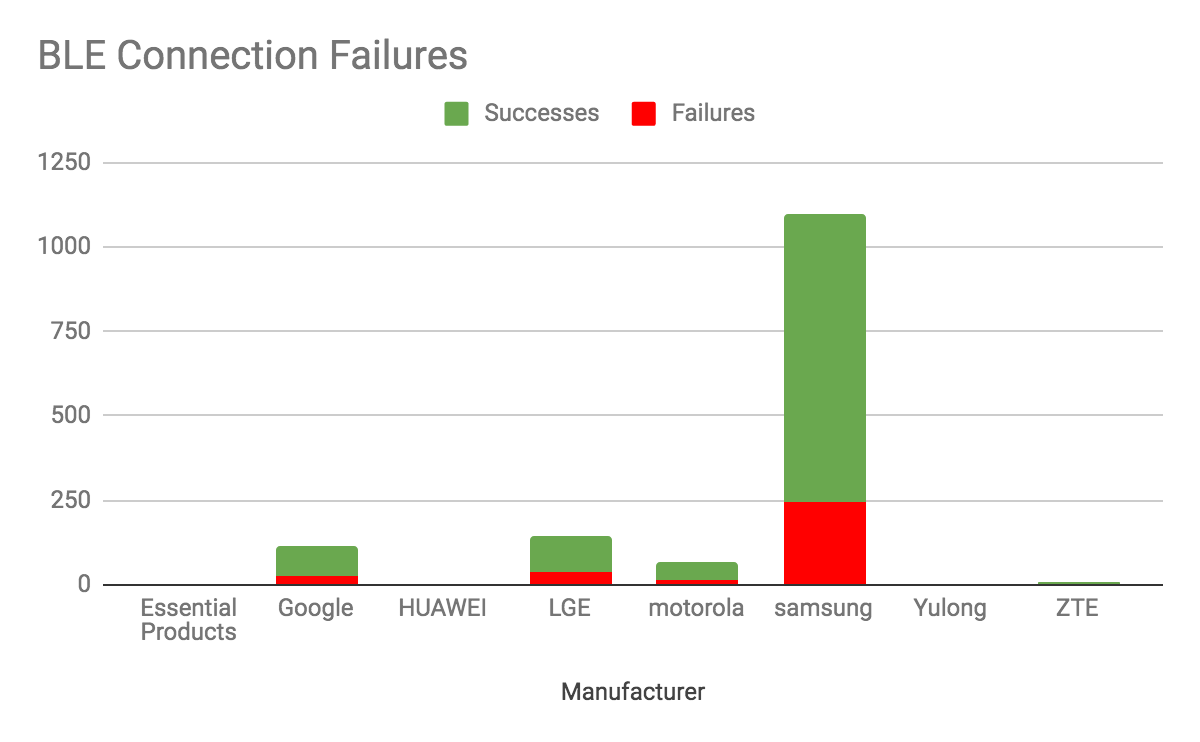

The detailed failure rates across Android models and operating system versions should be taken with a grain of salt. The data were collected at garages in and around Washington, DC where iPhones are far more prevalent than Android models, making the Android data points relatively sparse.

The more you drill down into the Android data, the fewer data points you have, making the statistical significance questionable. So while it is possible to conclude with confidence that Android is far worse than iOS and that things are not getting better, it is hard to say anything about which Android models and manufacturers are better than others.

For this reason, two versions of each graph are shown, one with total counts of successes and failures, and the other showing percentages. But because we have very few samples for the new Galaxy S10 or for Huawei and Yulong devices (rare in Washington, DC), don’t jump to conclusions about these outlier success and failure rates. When you see a count below 50 or so in the second graph, know that the percentages in the first graph really don’t mean anything.

Those caveats aside, for broader conclusions this data set is very useful. The Bluetooth service is identical in all cases. The radio distance and operating conditions are all very similar. The one variable that changes is the type of phone.

What’s Wrong With Android?

Clearly the problem is with Android as a whole, not with specific manufacturer implementations. There are a number ways the app can fail to communicate with the Bluetooth service, but looking at the error codes, by far the most common problem is establishing and maintaining a Bluetooth LE connection. On both iOS and Android, a Bluetooth LE GATT service communication sequence involves a number of steps:

-

The phone scans for and detects a nearby Bluetooth device

-

The phone connects to the device

-

The phone exchanges data with the device

-

The phone disconnects

On Android, the vast majority of the failures are on step 2. The connection attempts typically time out, although they sometimes fail with a connection error. The second most common problem is an unexpected disconnect while performing step 3. When either of these problems happen, the app is programmed to retry (up to 10 times), and it is not uncommon for the connection to fail several times in a row, or to have to repeatedly reconnect after an unexpected disconnect. These same things happen on both Android and iOS, but on Android these connection problems happen much, much more frequently.

What’s more, the success/failure rates mentioned above are not counted as failures in the data set used for comparison in this article if the data exchange ultimately succeeds on retires. Anecdotal testing shows that retries on iOS are rare but on Android extremely common. This means the raw Android failure rate is probably higher than 20 percent, and even in success cases, the common retries cause Android operations to be much slower than iOS.

Without a doubt, the Android Bluetooth stack has a much higher failure rate establishing a Bluetooth LE connection than iOS, and once it establishes one, it is much more likely to drop the connection.

I don’t know the specific reasons why this is true. A Bluetooth packet sniffer might reveal some insights, but it certainly wouldn’t help anything without changes to Android. These problems have been there since Bluetooth LE support was added in version 4.3 nearly six years ago. Clearly, fixing this is not high on Google’s priority list. Knowing the details of why it is unreliable won’t change anything for apps using public versions of Android.

UPDATE: Changes in Android 10 offer hope for the future

Is Bluetooth Useless on Android?

Unreliable as Bluetooth LE connections are, there is still plenty of use for Bluetooth on Android. Lots of functions like speakers use Bluetooth classic functionality and has nothing to do with Bluetooth LE connections. Not all Bluetooth LE use cases even require connections. Bluetooth LE Beacons, for example, are connectionless and work quite well on Android.

Some applications that rely on rare Bluetooth LE connections, like configuring a fitness tracker, work fine. You might have to hit retry a few times before it works. That is a bit annoying, but certainly acceptable.

But for use cases where frequent Bluetooth GATT connections are required and they needs to be fast and highly reliable, Android will likely disappoint. Imagine the stress of repeatedly seeing “connection failed” while tapping the exit button to get out of a parking garage as the cars keep lining up behind you. At least the driver can hit the intercom button for assistance. Other use cases don’t have that option.

What You Can Do

If you are designing a system using Bluetooth LE on Android, and it needs to be highly reliable, avoid Bluetooth LE connections if possible. Can you use one-way beaconing to accomplish your goal? If you can, do it.

If not, can you use two-way beaconing to accomplish your goal? While difficult to design, I have seen this approach work reliably. Unfortunately it is limited to low data throughput use cases.

If you cannot avoid Bluetooth LE connections, ask yourself this question: Is a 20 percent failure rate acceptable for my use case? Will my Android users be understanding if they sometimes have to hit retry a few times, and even then it still might not work? For some use cases, this still might be acceptable.

But for use cases where a high degree of reliability is critical, don’t even try it. The common approach to Bluetooth development is to build iOS first and then expect Android to be “just the same.”. That approach will not make you, your boss, nor your customers happy.

Addendum: Methodology Discussion

For those interested in further details about how the data were collected and a discussion of other possible explanations for the discrepancy between iOS and Android, read on.

One other thing that all Android devices used in this data set have in common that could contribute to the problem is the Android app code itself. Perhaps it is not Android at fault, but the programmer (me) who built the closed-source app in a way that made it buggy and unreliable. Like most engineers, I am always paranoid about possibilities like this. After reviewing Android BLE GATT programming best practices and pitfalls, I rewrote the app’s Android Bluetooth client to make extra sure these best practices were followed to the letter, being especially careful about thread handling. I then released an update to the Google Play Store and crossed my fingers for the failure rates to go down. They did not. While a few specific errors did decrease in frequency or go away entirely (those associated with threading on Android’s fiddly Bluetooth LE APIs), these were rare. What’s more, the fixes did not significantly affect the overall Android numbers. While other undiscovered bugs may certainly remain, the fact that I also wrote the reliable iOS app suggests that programmer error is unlikely to explain the difference between the iOS and Android error rates.

Could the Linux service be the culprit? Perhaps Linux does not like communicating with an Android client. The Linux computer is a Raspberry Pi 3 with a built in BLE controller, running the BlueZ Bluetooth stack, and the Node JS Bleno GATT module. The same code also runs on MacOS with a different Bluetooth chip, and a different Bluetooth stack. With the service running on MacOS, the system shows similar Android connection problems. I have also seen that these kinds of connection problems exist for Android on other projects I have built, using Bluetooth services hosted on Windows, iOS, MacOS, and embedded devices.