Can technology help save lives during the coronavirus pandemic? This exciting idea has inspired a number of urgent projects worldwide ranging from an open source ventilator to numerous contact tracing mobile apps.

The idea of contact tracing apps is simple: help people keep track of when they may have come in contact with others infected with novel coronavirus.

If one of the app users later tests positive for the novel coronavirus, the data collected by the app can be used to identify everybody who came in contact with the infected person, letting them know of the risk. A variety of apps released and in flight vary greatly by technologies used and how private data are managed, with the Singapore’s TraceTogether and MIT’s Safe Paths drawing a quick buzz. Not to be left out, Apple and Google announced they will work together to tie this functionality into their mobile platforms.

In this blog post, I evaluate the technical approaches used in the Singapore and MIT apps and analyze their potential effectiveness. I will then discuss proposals by Google and Apple may change the landscape.

TraceTogether (iOS and Android)

Developer: Singapore Ministry of Health

Availability: Currently released in the iOS and App Stores

Eligibility: Activation requires an SMS-capable phone with a +65 (Singapore) country code

Overview

The TraceTogether app works by silently finding other app users nearby, and recording when you came in contact with them. Looking at the user interface, you have no indication it is doing anything helpful – it just silently collects information. If you trust the app to do what it says, you might expect to get a call or text from the Ministry of Health if somebody you came near gets a positive coronavirus test result.

Technology

The developers give a basic overview of how they say it works:

TraceTogether uses Bluetooth to perform handshakes with other TraceTogether phones. Your Bluetooth-enabled phone is capable of connecting to multiple Bluetooth devices simultaneously, e.g. smart watch and wireless headphones. The different connections are separate and should not be affected by or affect TraceTogether… We use the Bluetooth Relative Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI) readings between devices across time to approximate the proximity and duration of an encounter between two users. This proximity and duration information is stored on one’s phone for 21 days on a rolling basis — anything beyond that would be deleted. No location data is collected.

Since the Android and iOS apps require a mobile phone with a Singapore country code to activate, I couldn’t experiment with them myself. And because the source code was not open source as of this writing (despite the authors’ promises to release it) the easiest way to see how it works is to analyze the Android APK file. This analysis reveals a number of insights:

- The app advertises a Bluetooth LE GATT Service that exposes readable characteristics. It does not use Bluetooth beacons, and its advertisements are not beacons because they do not contain a unique identifier.

- The app connects to each other device it sees that also hosts the app, reading a GATT characteristic to reveal a numeric identifier to identify the other user. This identifier is supposedly anonymized so only the Ministry of Health knows who it is.

- The signal strength on the Bluetooth connection during the communication gives an indication of how far the other person was away – e.g. more or less than 6 feet.

Adding a timestamp of when the user was detected, you end up with four pieces of information:

- Who the other user was

- About how far away that user was

- When the app came into contact with that user

- How long the apps were in proximity

By creating a log of this information, the app can (in theory) provide a pretty good record of who the user came into contact with.

That’s the theory. In reality, there are a number of flaws in its implementation that limit its usefulness. Let’s start with the fact that it doesn’t really work well on iOS:

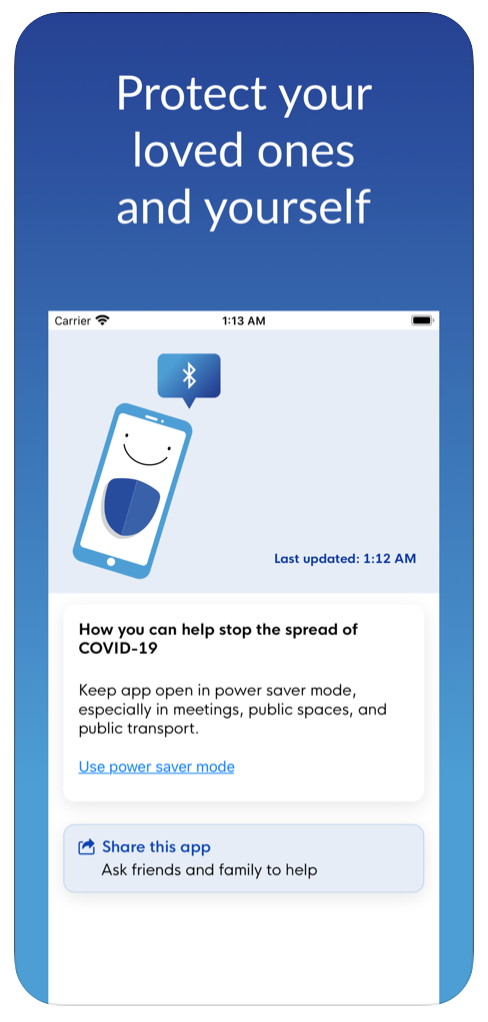

TraceTogether works best in the foreground. We recommend users keep TraceTogether open in meetings and crowded places. iOS users can also activate the in-app “Power Saver Mode” (see images) to keep TraceTogether in the foreground with a dimmed screen while communicating with other TraceTogether-enabled devices. TraceTogether Zendesk Site, as posted April 4 2020

Wow. Requiring users to keep the app visible in the foreground on their phone screens is a pretty big ask. Few people will actually do that.

Perhaps the development team cut corners on iOS because Apple only accounts for 35 percent of market share in Singapore. Android, they say, does work in the background. Except the problem there is that Android is notoriously unreliable when it comes to establishing the kind of Bluetooth connections the app requires. As I have documented in a prior blog post, the GATT service connection failure rate on Android devices is around 20 percent, even with retries.

So there is a 20 percent chance that an Android phone won’t be able to get the identity of other users in the vicinity even if they have the app. Likewise, other Android users have a 20 percent chance of not seeing your app. And that all assumes that everybody has the app installed properly, their batteries are charged, with Bluetooth on, location on, and proper permissions granted.

In practice, many of these things won’t be true, bringing the effectiveness rate probably well below 50 percent across both iOS and Android even for people who have it installed.

Data Collection

As soon as you launch the app, it prompts you to enter a Singapore phone number so you can receive an activation code via SMS message. Entering this SMS message will register your phone number (and presumably the app’s “anonymous” installation identifier that is shared with other app users in the vicinity) with the Ministry of Health. Supposedly, all of the data are then stored exclusively on your phone and are not shared without your consent.

All of this data is stored only on your phone, and not shared with MOH. Should MOH need the data for contact tracing, they will seek your consent to share it with them. TraceTogether Zendesk Site, as posted April 4 2020

In fact, you have no obvious way of accessing your own data as it is locked up inside your phone. Only the Singapore Ministry of Health can access these data, supposedly with your consent, perhaps in the case where you get a positive coronavirus test. This would allow health workers to de-anonymize the contacts inside your phone by linking them up with the phone numbers they collected, and enable them to alert them of their possible exposure.

Covid SafePaths (iOS and Android)

Developer: MIT

Availability: Currently released in the iOS and App Stores as “PrivateKit”

Eligibility: Open

Overview

This app relies entirely on tracking your location coordinates over time to remember where you have been over the past few weeks. Its current release doesn’t directly use Bluetooth or any other means to scan for other users in the vicinity. It is designed simply to record where you have gone so you can later know if you have crossed paths with somebody who has tested positive for the novel coronavirus.

Anybody who has ever used Google Timeline – a feature in Google Maps that tracks your location history – will be familiar with how this app works. You can see where you have been recently as measured by your phone’s location sensors.

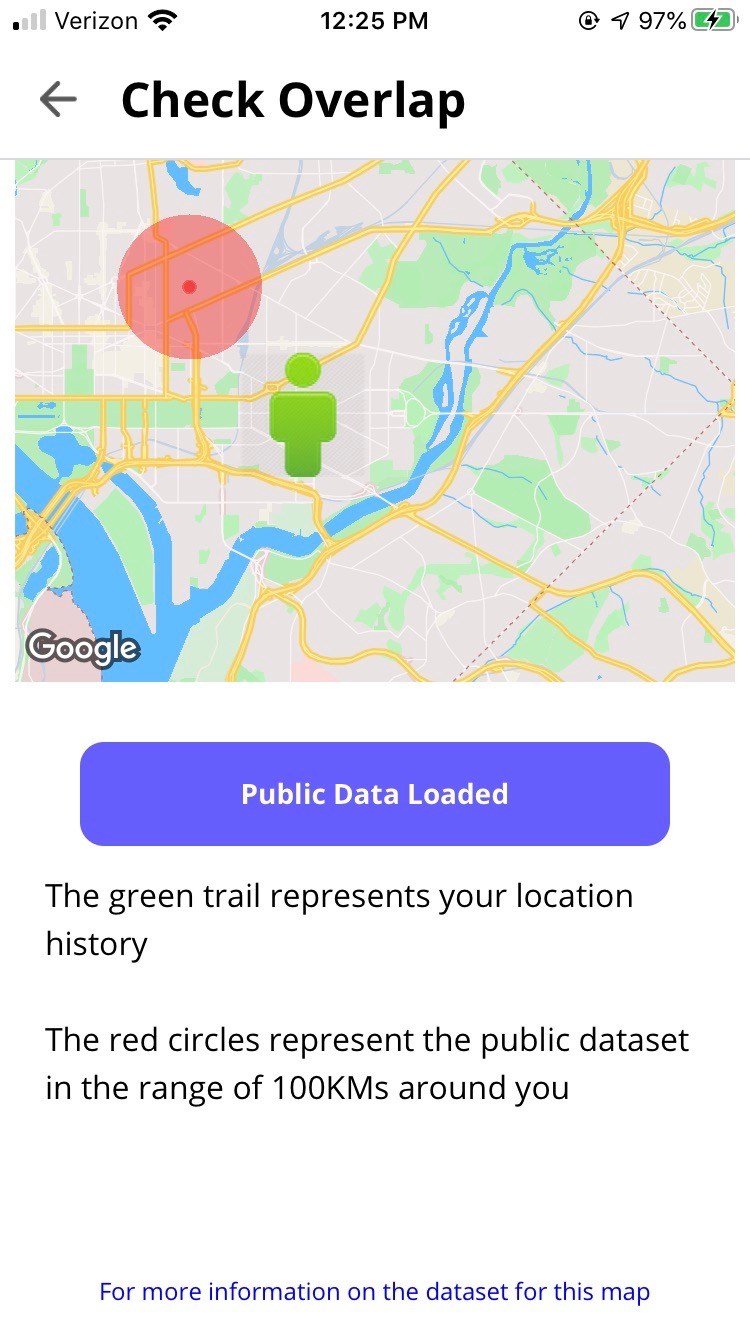

The contact tracing comes in when you try to match your path with publicly published paths of people who have tested positive for the novel coronavirus. These published paths can be from independent sources or from data exports from the app itself. The app doesn’t directly let you publish your path, but allows you to export your path for trusted sources to publish, presumably after they have confirmed your infection status.

The app has a feature where you can import these public data sets for your area and check for overlaps in time and space to where you have gone. The idea here is that you can compare where you have been at the same time with other folks who have tested positive, giving you an idea of where you have been put at risk.

Technology

Unlike Singapore’s Ministry of Health, the MIT initiative actually has released their code as open source, making it much easier to see what they are doing. The iOS and Android builds largely share a common codebase given that it is built on ReactNative. That is a real strength in the sense that it makes development faster, but it is quite limiting in the sense that it waters everything down to common functionality that both platforms can support in an equivalent way. That isn’t quite so important for location tracking, but it is important when you get into Bluetooth proximity.

And while the app doesn’t yet support detecting proximity to other users by Bluetooth, there are clearly plans to add this feature. A recent change added advertising of a custom Bluetooth beacon format that sends out a rotating universally unique identifier (UUID), and remembers what identifier the app was advertising at any given time. The rotation presumably is used as a privacy mechanism to prevent casual Bluetooth sniffers from tracking individuals using this rotating UUID, although rotation cannot protect against determined listeners.

Presumably, a future release will also add detection and tracking of these UUIDs, so you can tell who you came into contact with. But again, this has not been built yet. The idea may be to get the beacon transmitters out there now in case folks don’t upgrade the app later.

Aside from the fact that no Bluetooth detection has been built yet, there is another glaring hole in the app’s Bluetooth support. This Bluetooth advertisement is only enabled on Android. Why? Probably because iOS simply doesn’t let you advertise beacons when the app is in the background – you have to use other techniques to get around this. For these reasons it is unclear what this project hopes to accomplish with its Android-only advertisement, and whether it has any thoughts on how to deliver equivalent functionality on iOS.

But the bigger technical drawback is the entire path overlap approach. Location sensors on phones have quite poor accuracy in real world conditions. Sure if you have Google Maps running to give you driving directions, it’s pretty accurate. But that is because the GPS is fired up at a 100 percent duty cycle the whole time. An app simply can’t keep this going in the background without draining the user’s battery quickly. Folks who use driving directions on a long road trip know that they need to keep the phone charging to keep it from going dead.

The app is designed to save your battery by only passively using location sensors. When you aren’t using the GPS for other purposes like driving directions, it shuts off, falling back to secondary location sensors: WiFi hotspots, Bluetooth beacons or cell towers. Accuracy drops from a few meters down to tens or hundreds of meters. The app might know you were in a supermarket at a specific time of a specific day, but it has no idea where you were in that supermarket.

So, by itself, this kind of information isn’t very useful for contact tracing. Without the GPS being on (which it almost never is) the app can’t tell you if you were ever within, say, 6 feet of an infected person. While it might tell you if you were once in the same building at the same time as somebody else who tested positive, in any city with a significant infection rate, this condition would be true for a very large percentage of people. The bottom line is that the technology employed so far is way too prone to generating false positives.

Data Collection

Where the MIT app shines is in privacy protection. Unlike Google Timeline, the MIT app doesn’t share your entire location history with the Silicon Valley behemoth. They don’t require registration with any servers, and they claim that your entire history is only stored locally on your phone. Only you can decide you want to share the data it collected, perhaps in the event that you test positive and want to help warn other folks by publishing where you’ve been.

But while this privacy protection is laudable, the fact that the app’s current technology does not allow effective contact tracing means that the MIT app is little more than an academic exercise in privacy protections in a location app.

Is This the Best We Can Do?

Both of these apps have gotten a lot of attention, but given the quality of what they do, this attention isn’t really deserved.

Singapore’s Ministry of Health got attention because they were the first to release an app. They got more attention by promising to release it as “open source” – something they still haven’t done three weeks later as of this writing. (EDIT: the code has now been posted here) The iOS version of the app expects users to leave their phone turned on all the time with the app visible on the screen for “best” results. Without a proper design that allows iOS Bluetooth tracking to work in the background, their app design is simply a non-starter.

The MIT app, meanwhile, has no working Bluetooth tracking at all, relying instead on inaccurate location measurements typically without aid of the battery-hungry GPS radio. This simply isn’t accurate enough to be a useful contact tracing tool.

There are other apps out there, too, that have been more solid in their technical approach. A Stanford University effort called Covid Watch, for example, tries to work around the distinct Bluetooth limitations of Android and iOS by building a system that uses the best of each platform’s capabilities, and uses tricks to make them cooperate when both kinds of devices are nearby. But even this approach still relies on unreliable GATT connections on Android.

Make no mistake: contact tracing apps can do better. It is possible for both Android and iOS apps to use Bluetooth to both advertise in the background and simultaneously scan for other devices doing the same. It is possible to measure with some degree of certainty if they are less than 6 feet apart. Apps can do this without requiring unreliable GATT connections on Android and without relying on background beacon broadcasts currently impossible on iOS. Such apps can record these identified devices in a privacy-friendly way, allowing a reliable way of later finding contacts that might have spread the disease.

The Problem of Adoption

No matter how good the technology of an app, there must be common adoption for it to make a difference. If only 1 percent of people in a city install a particular contact tracing app, it simply won’t be useful. Even if 60 percent of people install apps, they still won’t be useful if they are fragmented between several different apps that don’t work together. The well-meaning efforts by dozens of app developers to build contact tracing efforts may be for naught.

Apple and Google’s Response

On April 10, Apple and Google issued a joint statement that they will produce APIs that work on both platforms for Bluetooth contact tracing. The common system plans to rely on a custom Bluetooth beacon advertisement with a rotating identifier, and always-on operation for users who opt-in. This system would eliminate many of the technical problems of the apps described above. The companies pledge to have an app available by sometime in May.

![]()

But here’s the elephant in the room: the proposal is impossible to implement on today’s iPhones installed with the latest iOS 13.4.1. The operating system has for years prohibited exactly the kind of Bluetooth advertisement mentioned in the proposal. That means Apple has to change their operating system for this to work. They then need to release the operating system (iOS 13.2?), get people to install it, and opt-in to the process. Given that over 90 percent of iPhone users typically upgrade to the latest operating system, this may eventually work out OK. But this will still take time, and not everybody will install the upgrade.

On Android, no new operating system changes are required. An app meeting the specifications can be built today (see how in the next blog post), although it may have trouble staying running in the background on cheaper phones models with custom battery savers. The biggest obstacle on Android is interoperability. Until Apple gets an operating system update out there, Android-only solutions will work poorly in places like America, where iPhones are popular, especially in coastal cities. A system that helps alert you to exposure from only half the people you encounter isn’t very useful.

It’s Still Worth Trying

No app can ever hope to provide a perfect solution. Bluetooth stacks sometimes go down. Phone batteries sometimes go dead. Even well-designed apps sometimes crash.

It’s not surprising that well-meaning teams, building as quickly as possible to get apps to the public, have not yet approached what’s achievable. Developers must temper their enthusiasm to build something in favor of solutions that can actually make a difference. But that shouldn’t stop us all from trying.