When Google and Apple announced a common specification for pandemic contact tracing on April 10, it offered hope for a universal system. Currently, dozens of projects around the world are working on mutually incompatible systems, specifically targeting national populations, individual provinces or even employees of specific companies.

The big problem with proposals from Google and Apple is that they are so far just vaporware. Promised SDKs have not been published as of this writing, and cannot be used. (UPDATE 4/30/2020: Apple released SDKs in XCode 11.5 beta for running on iOS 13.5 beta 2.) What’s more, the latest version of iOS, 13.4.1 disallows transmitting the Exposure Notification Service beacon bluetooth advertising packet in the common specification. Apple will have to release a 13.5 version of iOS before this will work. When Apple’s SDK is released and delivered with in a future version of XCode, Apple is expected to block direct transmission and detection of this beacon format by third party apps, forcing them to use higher-level APIs. (UPDATE 4/30/2020: This expected blocking is in place as of iOS 13.5 beta 2.)

Android, however, is another story. While Google has likewise not released any new SDKs that support the proposed APIs (although a Google Play Services update is expected for this), Android already supports sending and detecting the Exposure Notification Service beacon advertisement that the bluetooth specification envisions.

Exposure Notification Service Beacon

The common system relies on a bluetooth packet that will be sent out of both Android and iOS phones. The packet is a GATT service advertisement with attached data and looks like this:

| length | type | UUID | length | type | UUID | rolling proximity identifier | metadata |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x03 | 0x03 | 0xfd6f | 0x17 | 0x16 | 0xfd6f | 16 bytes | 4 bytes |

The 16-bit GATT service UUID, 0xfd6f identifies a transmission from the phone as an Exposure Notification Service advertisement (formerly known as the Contact Detection Service until a recent rebranding – do marketing folks think “detection” is a naughty word?). The 16 bytes of attached data is the identifier of the transmitting device – a “rolling proximity identifier” as the spec describes. An app transmitting this packet is supposed to change this identifier every 15 minutes based on a cryptographic algorithm. The final four bytes are “encrypted metadata” which include versioning information as well as a tx power value that indicates how strong the bluetooth signal might be at a known distance. GATT service advertisements are typically used to advertise connectable Bluetooth LE GATT services – a little program that you can connect to over bluetooth, and exchange data. But i this case, there is no such service. The advertisement itself indicates it is not connectable. The entire purpose of the advertisement is to announce its presence and deliver this identifier. It is therefore a Bluetooth LE beacon advertisement, much like Google’s Eddystone family of Bluetooth beacon advertisements that also are based on GATT service advertisements.

Exposure Notification Beacons in Action

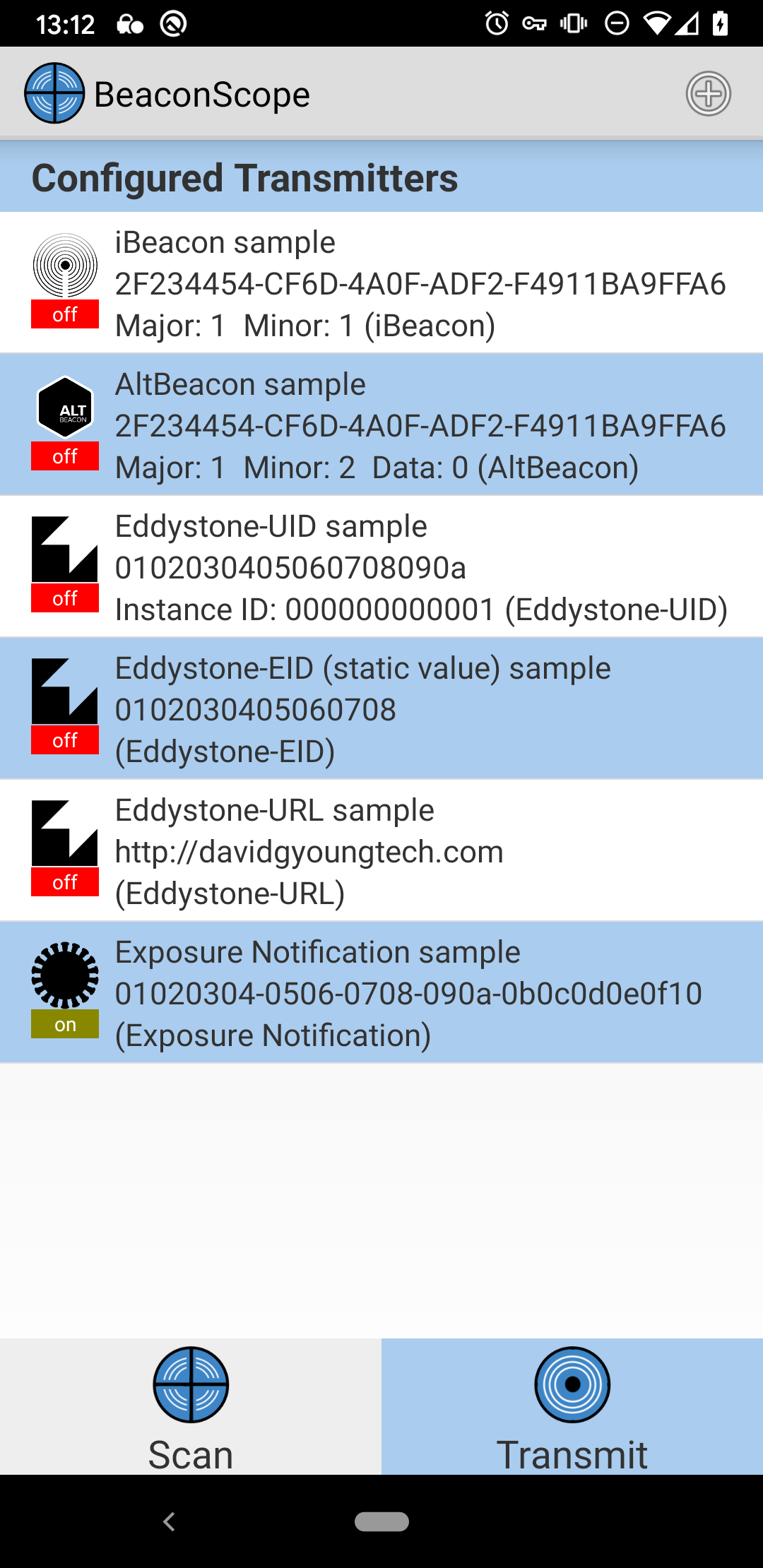

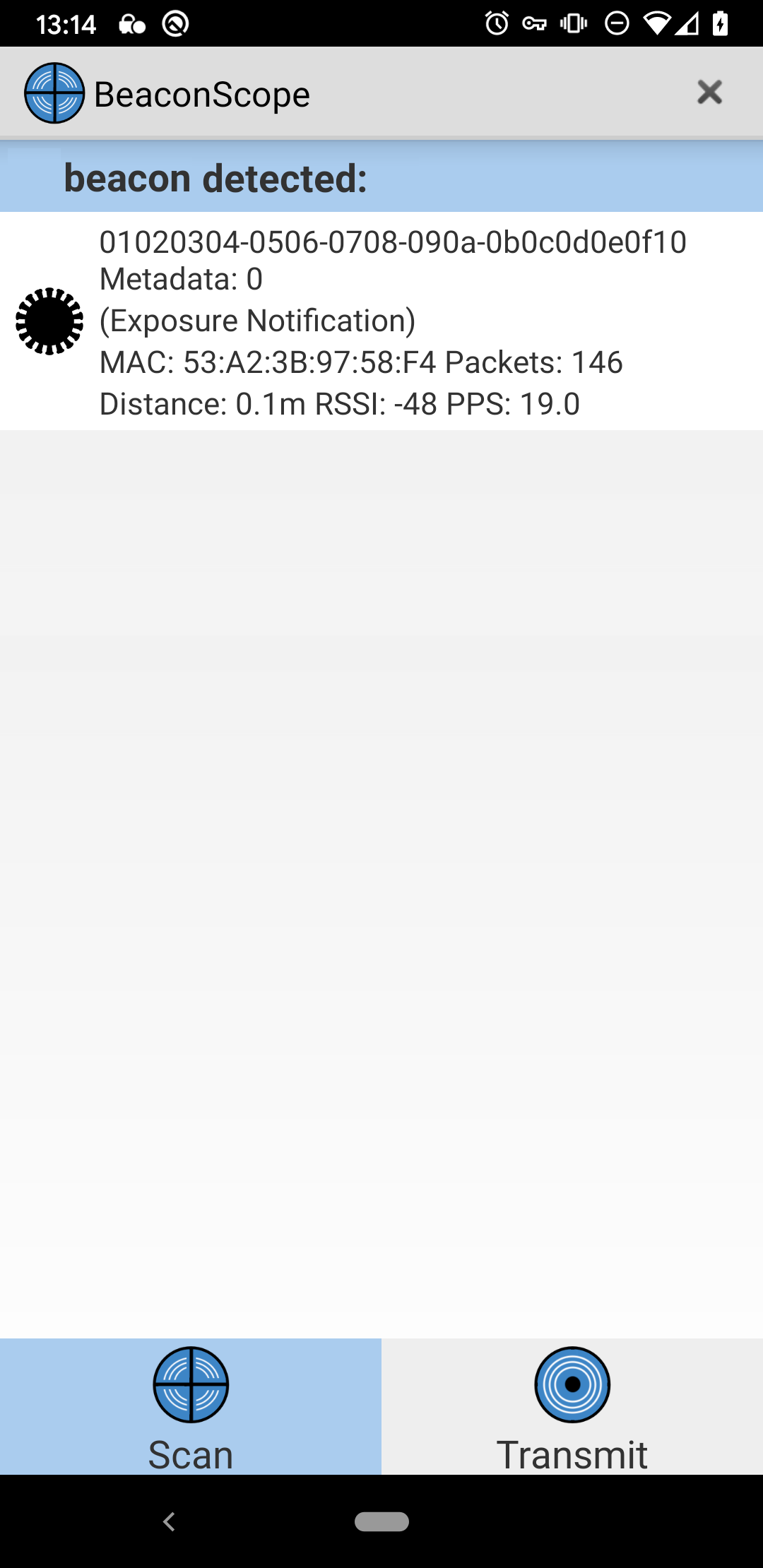

Today, you can use the free and open-source Android Beacon Library to send and receive this beacon format. You can even try it out without writing any code by using my off-the-shelf BeaconScope mobile app. This app is based on the same library, and can both send and receive this Exposure Notification Service beacon advertisement.

Making Your Own App

If you wan to write your own app to do this, then you need the 2.17 version of the Android Beacon Library. With that you can make a transmitter like this:

String uuidString = "01020304-0506-0708-090a-0b0c0d0e0f10";

Beacon beacon = new Beacon.Builder()

.setId1(uuidString)

.build();

// This beacon layout is for the Exposure Notification service Bluetooth Spec

BeaconParser beaconParser = new BeaconParser()

.setBeaconLayout("s:0-1=fd6f,p:-:-59,i:2-17,d:18-21");

BeaconTransmitter beaconTransmitter = new

BeaconTransmitter(getApplicationContext(), beaconParser);

beaconTransmitter.startAdvertising(beacon

That layout string above is what tells the library how to understand this new beacon type. The layout “s:0-1=fd6f,p:-:-59,i:2-17,d:18-21” means that the advertisement is a gatt service type (“s:”) with a 16-bit service UUID of 0xfd6f (“0-1=fd6f”) and it has a single 16-byte identifier in byte positions 2-17 of the advertisement (“i:2-17”) and a 4-byte data field in positions 18-21 (“d:18-21”). The “p:-:-59” indicates that there is no unencrypted measured power calibration reference transmitted with this beacon, and the library should default to using a 1-meter reference of -59 dBm for its built-in distance estimates. You can use similar code to detect these beacons like this:

BeaconManager beaconManager = BeaconManager.getInstanceForApplication(this);

beaconManager.getBeaconParsers().add(new BeaconParser().setBeaconLayout("s:0-1=fd6f,p:-:-59,i:2-17,d:18-21"));

...

beaconManager.startRangingBeaconsInRegion(new Region("all exposure beacons", null));

...

@Override

public void didRangeBeaconsInRegion(Collection<Beacon> beacons, Region region) {

for (Beacon beacon: beacons) {

Log.i(TAG, "I see an Exposure Notification Service beacon with rolling proximity identifier "+beacon.getId1());

}

}

You can also make the above transmitter and receiver work indefinitely in the background by using a Foreground Service. The library documentation describes how to set this up here.

What the above shows is just raw transmission and reception. It doesn’t show is how to handle the “rolling proximity identifiers” inside these beacons.

How the Identifiers Work

Much of the proposal from Android and Apple is devoted to how to handle these identifiers in a decentralized privacy-friendly way. The transmitted “rolling proximity identifier” is a 16-byte GUID. But each app transmitter is supposed to change its transmitted identifier approximately every 15 minutes. At any given time, a single device’s identifier is based on a temporary exposure key (which the phone generates and stores daily), and a cryptographic algorithm that makes a 16-byte “rolling proximity identifier” based on this temporary exposure key.

Because the identifiers appear to be randomly changing every 15 minutes, it is supposed to be impossible to tell which identifiers came from which device (or even which rotated identifiers came from the same device) – unless you have the device’s daily key.

If medical tests confirm that a device’s owner is infected with novel coronavirus, that owner can optionally publish his or her temporary exposure keys from the last few weeks. These temporary exposure keys allow all other mobile phones in this system to look for a match. The apps on these phones can then re-run the cryptographic algorithm with these published keys, allowing it to see if any of the “rolling proximity identifiers” match ones send out by the device owned by the infected user. If there is a match, the app knows the specific time when it saw the infected user, for how long, and how strong the bluetooth signal was at those times, giving an idea of how close the two people came.

Can You Build Your Own Implementation?

On Android, yes, you can roll your own implementation of this today. In addition to the transmitter and receiver code shown above, you will also need to create your own implementation of the key generation, identifier rotation, key sharing and matching algorithm.

There are lots of reasons you might want to do so:

- You want a test tool to see how this system works, or to see if nearby devices are using it.

- You don’t want to wait for Google Play Services update with Google’s implementation, and want to make your own now.

- You want to provide an implementation for Android users who will never get the Google Play Services update. (e.g. Phones sold in China, Amazon Fire Tablets, newer Huawei phones sold outside China.)

- You want to build this into your own app so if users don’t update Google Play Services, or deny it permission to perform this function, your app can still provide the functionality.

If you decide to proceed, be forewarned that the spec is not final, so it may be subject to change. In the past few days, the spec was updated to add the Encrypted Metadata field and change much of the terminology.

Multiple Installations on the Same Phone

If you do build your own implementation, and a user later installs both your version and that inside Google Play Services, both will work at the same time. To other devices, two implementations on a single phone will appear to be two different phones (although over short intervals they will share the same bluetooth MAC address so it is theoretically possible to know they are the same phone.) The consequences of two copies running on the phone are little different than carrying two phones in your pocket.

Hacking on iOS

Equivalent hacking on iOS is currently impossible – at least on the transmission side. Apple’s iOS APIs prevent any 3rd party app from making the phone transmit the kind

of advertisement shown in the spec. While apps can transmit GATT service advertisements, they can’t attach data. This is because the CBAdvertisementDataServiceDataKey that associates service data to an advertisement is read-only on iOS. You simply can’t set the data needed to advertise one of these beacons.

What iOS can do is detect such advertisements with CoreBluetooth – for now at least. (UPDATE 4/30/2020: This no longer works on iOS 13.5 beta 2. It works on earlier OS versions.) Here’s code that shows how you can do that:

let exposureNotificationServiceUuid = CBUUID(string: "FD6F")

centralManager?.scanForPeripherals(withServices: [exposureNotificationServiceUuid], options: [CBCentralManagerScanOptionAllowDuplicatesKey: true])

...

func centralManager(_ central: CBCentralManager, didDiscover peripheral: CBPeripheral, advertisementData: [String : Any], rssi RSSI: NSNumber) {

if let advDatas = advertisementData[CBAdvertisementDataServiceDataKey] as? NSDictionary {

if let advData = advDatas.object(forKey: CBUUID(string: "FD6F")) as? Data {

let hexString = advData.map { String(format: "%02hhx", $0) }.joined()

let proximityId = String(hexString.prefix(32))

let metadata = hexString.suffix(8)

NSLog("Discovered Exposure Notification Service Beacon with Proximity ID\(proximityId), metadata \(metadata) and RSSI \(RSSI)")

}

}

}

The code above shows you how to start a scan for a service advertisement of the proper FD6F type. When one is detected, it then pulls out the service advertising data and splits it into the proximity id and metadata from the spec, and prints these out has hex bytes to the log.

There are a few caveats to this code:

- It will only receive constant updates when the app is in the foreground – meaning the device screen is unlocked, turned on and the app is visible.

- In the background, the app will get at most one detection callback. That is because iOS ignores the

CBCentralManagerScanOptionAllowDuplicatesKeywhen an app is not in the foreground, and only gives you the first detection. While this is good enough to build a scanning test tool on iOS, it makes it impossible for third party apps to develop background detectors.

There is also some risk that a future iOS update will block the above code from working. An iOS update expected in May will make the operating system (but likely not 3rd party apps) be able to transmit the new beacon type. But it is also likely that iOS will update CoreBluetooth in this same release to filter out receiving these advertisements using code like shown above, so it no longer works. (UPDATE 4/30/2020: Indeed, this blocking is confirmed as of iOS 13.5 beta 2.) Apple did exactly that for iBeacon advertisements. CoreBluetooth APIs filter out any data bytes matching the iBeacon advertisement spec – the array of advertising data is truncated to zero bytes. Time will tell, but it is entirely likely they will do the same for this new beacon type.

Is It Safe to Hack With This?

One good thing about Apple and Google’s system is that it is resistant to interference. In general, you don’t need to worry about causing problems by building an Android app that transmits garbage identifiers. While other phones using the system will store your garbage identifiers, and they will take up a tiny amount of space on phones, they will never match a reported positive contact, so the consequences will be nil.

Hack Responsibly

While it is safe to experiment, with enough effort, it is possible to maliciously try to interfere with the system. You could, for example, build an app that listens for real identifiers from these beacons in one location, then send them over the internet to a different phone, then re-transmit them in another location. Such a “replay attack” would make the system believe that one person was in contact with people in a different location. In most cases, this wouldn’t really matter, but it could affect individual contact reports. And if done on a broad scale, it could make the system less reliable. Please don’t do that.